My Research

My research interests have been in understanding the physics of rare and extreme astronomical transients. By observing the “edges” of transient physics, we can access some of the most poorly understood aspects of the evolution of massive stars: mass loss through winds and eruptions, magnetic fields, binary interaction, etc. This in turn teaches us what is normal and what is possible among massive stellar populations, and has implications in many other fields of astronomy, such as chemical and energetic enrichment in galaxies.

Progenitors of Thermonuclear (Type Ia) Supernovae

Light curve of SN 2017cbv. The U-band bump during the first five days may indicate the presence of a nondegenerate binary companion. Figure from Hosseinzadeh et al. 2017, ApJL, 845, L11.

Type Ia supernovae are the thermonuclear explosions of white dwarf stars in a binary system. However, the nature of the binary companion has been debated for several decades: it may be a nondegenerate main sequence or giant star, or it may be another white dwarf. Understanding the physics of Type Ia progenitors has the potential to improve their application as standard candles for cosmology, as well as shed light on some of the uncertainties in binary stellar evolution.

One of the most promising probes of Type Ia supernova progenitors is their early light curve behavior. If the binary companion is nondegenerate, it may be possible to see the ejecta-companion collision in the form of a blue excess in the early light curve. Such an excess has been observed in a handful of analyses, including two of my own, which are among the best sampled early Type Ia data sets. However, the interpretation of these excesses is complicated by the fact that we do not know the behavior of the underlying explosion in very much detail. For example, excesses may also be produced by an unusual distribution of radioactive nickel in the ejecta, explosions of white dwarfs below the Chandrasekhar mass, or interaction with circumstellar material. Furthermore, nebular spectroscopy of Type Ia supernovae rarely shows signatures of the hydrogen-rich material expected to be stripped from a nondegenerate companion, even when the light curve shows an early bump.

- “Early Blue Excess from the Type Ia Supernova 2017cbv and Implications for Its Progenitor,” ApJL, 845, L11

- “Constraining the Progenitor System of the Type Ia Supernova 2021aefx,” ApJL, 933, L45

- “The Early Light Curve of SN 2023bee: Constraining Type Ia Supernova Progenitors the Apian Way,” ApJL, 953, L15

Mass Loss in Core-Collapse Supernova Progenitors

Mass loss in massive stars is among the most poorly understood aspects of stellar evolution. Several lines of evidence point to circumstellar material around many if not most massive stars, even down to the tamest red supergiants. Core-collapse supernovae are uniquely powerful probes of mass loss because their observables can reveal material previously ejected by their progenitors. For a small number of supernovae, these mass loss events have been directly observed as outbursts at the supernova position before explosion

The most direct indication of circumstellar material in core-collapse supernovae, and indeed the first indication historically, is the presence of narrow emission lines in their optical and UV spectra, where the width of the emission lines corresponds to the wind or eruption speed (∼100–1000 km/s). In most cases, these lines disappear just a few days after explosion, once the supernova ejecta (moving at ∼10,000 km/s) sweep up the slower material. The lines from helium and CNO elements, highly ionized by photons either from the shock breakout or the shock interface between the ejecta and the circumstellar material, contain a wealth of information about the circumstellar material. Modeling of the flash spectra with non-LTE radiative-transfer codes like CMFGen can reveal the density and composition of the material and the nature of the ionizing radiation field. Then, by playing the “video” of circumstellar interaction in reverse, we can obtain the full mass-loss history of the progenitor star. I led two analyses whose goal was to map out the diversity of circumstellar material around core-collapse supernova progenitors: one showed unexpectedly strong interaction, and the other unexpectedly weak interaction.

- “Short-lived Circumstellar Interaction in the Low-luminosity Type IIP SN 2016bkv,” ApJ, 861, 63

- “Weak Mass Loss from the Red Supergiant Progenitor of the Type II SN 2021yja,” ApJ, 935, 31

- “Shock Cooling and Possible Precursor Emission in the Early Light Curve of the Type II SN 2023ixf,” ApJL, 953, L16

Spectra of SN 2016bkv from Las Cumbres Observatory's FLOYDS spectrograph. Narrow high-ionization lines (helium II, carbon III) that disappear after a few days, giving way to a typical low-velocity Type II supernova spectrum. Data from Hosseinzadeh et al. 2018, ApJ, 861, 63.

A Sample of Rare Type Ibn Supernovae

Type Ibn supernovae, which show narrow helium lines in their spectra (and no hydrogen), are a rare and poorly understood class of interacting supernovae. Our paper combined photometry and spectroscopy on six new events with all other events from the literature to form the largest-yet sample of Type Ibn supernovae. We found that, unlike other interacting supernovae, Type Ibn supernovae evolve quickly, rising in a few days and declining at a rate of 0.1 mag/day. Their light curves are homogeneous (with a few exceptions) but their maximum-light spectra can either show P Cygni lines on a blue continuum or more complicated emission features. This may be evidence for diversity in the progenitor state at the time of explosion: either two discrete states or a continuum of properties.

One of the Type Ibn supernovae in our sample, PS1-12sk, exploded in a giant elliptical galaxy. Non-star-forming host galaxies are exceedingly rare (<1%) for a core-collapse supernova, since massive stars have relatively short lifetimes. My Cycle 25 program on the Hubble Space Telescope found no star formation near the explosion location of PS1-12sk down to very deep limits, implying that Type Ibn supernovae may not all come from massive stars. If this is the case for a significant fraction of Type Ibn supernovae, we must reevaluate the conclusions about mass loss that we draw from this class of supernova.

- “Type Ibn Supernovae Show Photometric Homogeneity and Spectral Diversity at Maximum Light,” ApJ, 836, 158

- “Type Ibn Supernovae May not all Come from Massive Stars,” ApJL, 871, L9

Type Ibn light curve templates compared to analogous Type Ib/c templates (Nicholl et al. 2015; Taddia et al. 2015) and light curves of Type IIn (Kiewe et al. 2012; Taddia et al. 2013, and references therein) and Type Ia-CSM (Silverman et al. 2013, and references therin) supernovae. The upper panel shows the comparison of absolute magnitudes, and the lower panel illustrates the comparison when all light curves are normalized to peak. Type Ibn supernovae are much more homogeneous and faster evolving than other interacting supernovae. Figure from Hosseinzadeh et al. 2017, ApJ, 836, 158.

Power Sources of Superluminous Supernovae

What powers the luminous and long-lasting light curves of hydrogen-poor superluminous supernovae? Most of the current literature focuses on a newly born magnetar that injects energy through magnetic interactions at the center of the ejecta as it spins down. However, theory predicts this to be a smooth process.

In the first systematic study of the light curve behavior of superluminous supernovae at late times, we found that the majority do not decline smoothly. This is in direct conflict with the magnetar model: either we are missing a piece of physics in the magnetar–ejecta interaction, or the bumps arise when ejecta collide with clumps or shells of circumstellar material. To differentiate between these two possibilities, I modeled the light curves with the magnetar model plus a generic Gaussian excess and measured correlations between the magnetar parameters and the bump parameters. The strongest correlations are between the phase of the bump and the rise time. If the excess is intrinsic to the central engine, the positive correlation with rise time could indicate a drastic change in opacity as the ejecta cool past a certain temperature. In either case, more theoretical work is needed to understand the relevant stellar physics, both before and after explosion.

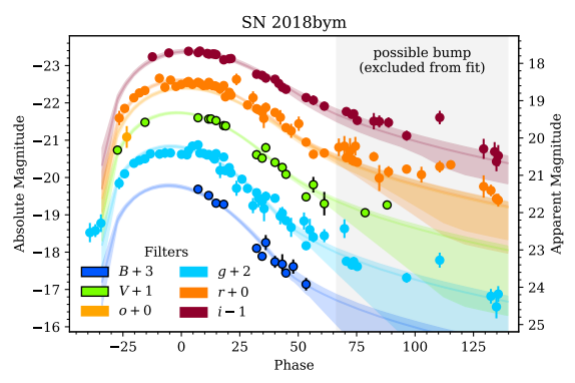

Magnetar model (colored regions) fit to the multiband observations of the superluminous supernova SN 2018bym with significant residuals ∼120 days after peak. After identifying this “bump” (gray region), we redo the fit to the remainder of the data and model the residuals with a Gaussian to characterize its amplitude, phase, and color. Figure from Hosseinzadeh et al. 2018, ApJ, 933, 14.

Optical Follow-Up of Gravitational Waves

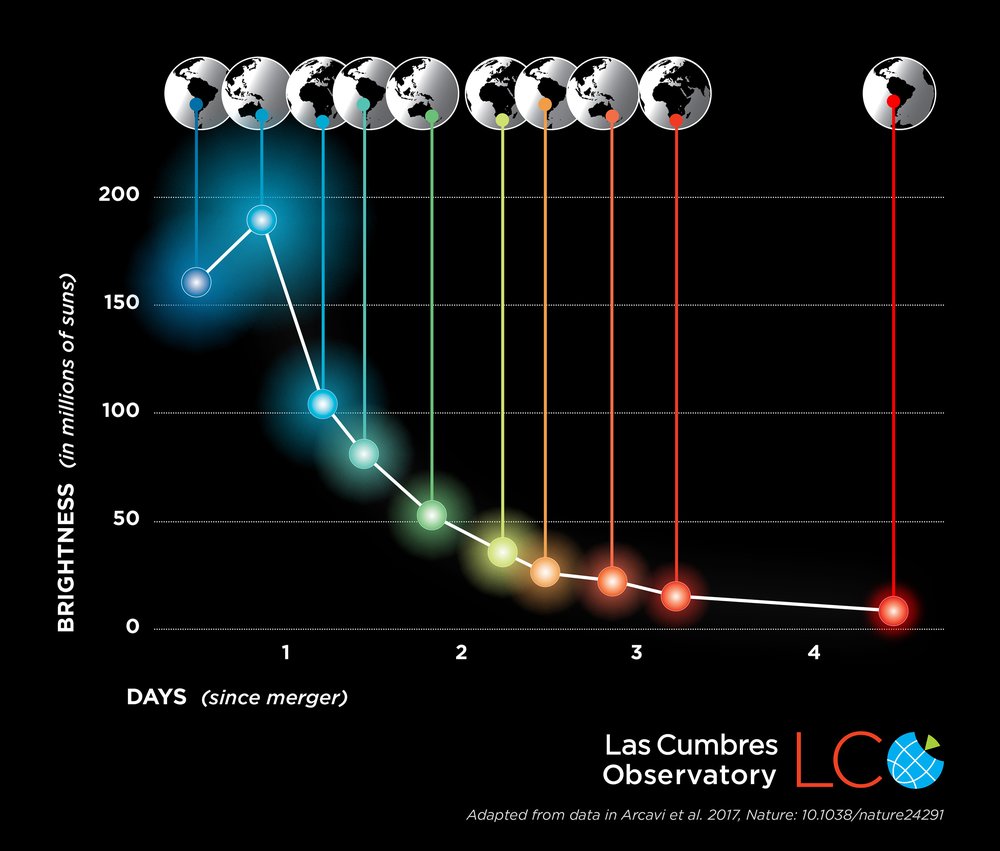

I was part of the group at Las Cumbres Observatory that independently discovered the optical counterpart of the binary neutron star merger, called a kilonova. The kilonova became red and faded by a factor of over 20 in just a few days. This rapid change was captured by Las Cumbres Observatory telescopes as nighttime moved around the globe. Credit: Sarah Wilkinson/LCO

The detection of the first kilonova from the binary neutron star merger GW170817 was a watershed event. From this one event, we learned that neutron star mergers produce γ-ray bursts and gravitational waves, and that they form low-mass black holes. We also learned that kilonovae may dominate r-process nucleosynthesis in the Universe. However, several open questions remain, including the initial nature of the remnant (is there a short-lived hyper-massive neutron star before forming a black hole?) and the mechanism behind the early blue emission. Of course, with only a single event to constrain our theories, the biggest open question is how the parameters of the progenitor system (e.g., masses, viewing angle, environment) will map to diversity among kilonova observables.

The key to differentiating between these models is very early observations. The low-opacity component in particular only dominates kilonova emission for the first ∼2 days after merger, and various models (e.g., radioactive decay and/or shock cooling) that initially make very different predictions for kilonova luminosity converge after only 1 day. This presents at least three challenges: (1) the community must identify the kilonova corresponding to a given gravitational-wave event from among the potentially dozens of active transients; (2) follow-up observations must start immediately after announcement of the kilonova candidate(s) and continue at high cadence; and (3) the observations must be deep enough to detect the kilonova at distances of 100–200 Mpc and possibly before maximum light. As the leader of the SAGUARO Collaboration’s GW follow-up efforts, I am preparing us to meet all these challenges by building both hardware and software infrastructure, as well as laying out complex observing strategies, well in advance of the fourth gravitational-wave observing run, as I did for the CfA gravitational-wave follow-up collaboration during the previous observing run.

- “Optical emission from a kilonova following a gravitational-wave-detected neutron-star merger,” Natur, 551, 64

- “Follow-up of the Neutron Star Bearing Gravitational-wave Candidate Events S190425z and S190426c with MMT and SOAR,” ApJL, 880, L4

- “SAGUARO: Time-domain Infrastructure for the Fourth Gravitational-wave Observing Run and Beyond,” ApJ, 964, 35

Photometric Classification with Machine Learning

The number of supernovae close enough to get a spectrum within several days of explosion is small and will remain so even in the era of Legacy Survey of Space and Time at Vera C. Rubin Observatory. Therefore, in addition to intense spectroscopic follow-up of nearby supernovae, progress demands that we analyze the sample of millions of supernova light curves from LSST. With existing spectroscopic resources, we will only be able to spectroscopically classify ∼0.1% of transients. We must instead rely on survey photometry alone to classify the remaining 99.9% of discoveries. To that end, I have developed Superphot, a machine-learning-based photometric classifier trained on the Pan-STARRS1 Medium Deep Survey that achieves a 90% (98%) pure sample of Type II (Type Ia) SNe among high-confidence classifications. An undergraduate under my supervision carried out the first scientific analysis of photometrically classified superluminous supernovae using Superphot and its semisupervised counterpart SuperRAENN.

- “Photometric Classification of 2315 Pan-STARRS1 Supernovae with Superphot,” ApJ, 905, 93

- “SuperRAENN: A Semisupervised Supernova Photometric Classification Pipeline Trained on Pan-STARRS1 Medium-Deep Survey Supernovae,” ApJ, 905, 94

- “Photometrically Classified Superluminous Supernovae from the Pan-STARRS1 Medium Deep Survey: A Case Study for Science with Machine-learning-based Classification,” ApJ, 937, 13